|

| Situation Awareness: Recognizing Changing Critical Infrastructure and Need(s) to Act |

|

| |

|

| |

| What is Situation Awareness? |

| |

What’s a mountain goat doing in the clouds?

|

| |

| What is Situation Awareness? |

| |

|

| |

| What is Situation Awareness? |

| |

I’ll tell you what it means, Norm. No size restrictions and forget about the limit…

|

| |

Situation Awareness (SA)

- “Situation awareness is the perception of the elements of the environment within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in the near future.” Mica R. Endsley, Human Factors 37 (1995) 32-64.

- A state of knowledge

- Situation Assessment: “the process of achieving, acquiring, or maintaining SA [situational awareness].”

|

| |

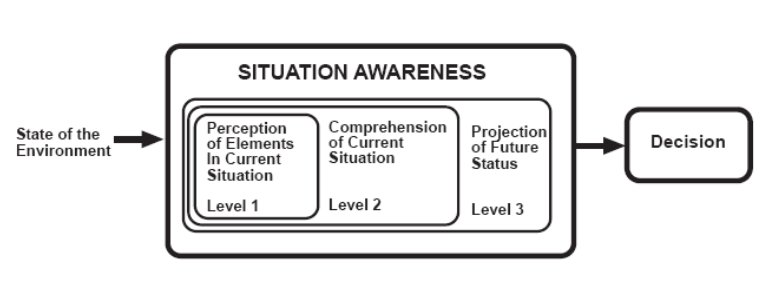

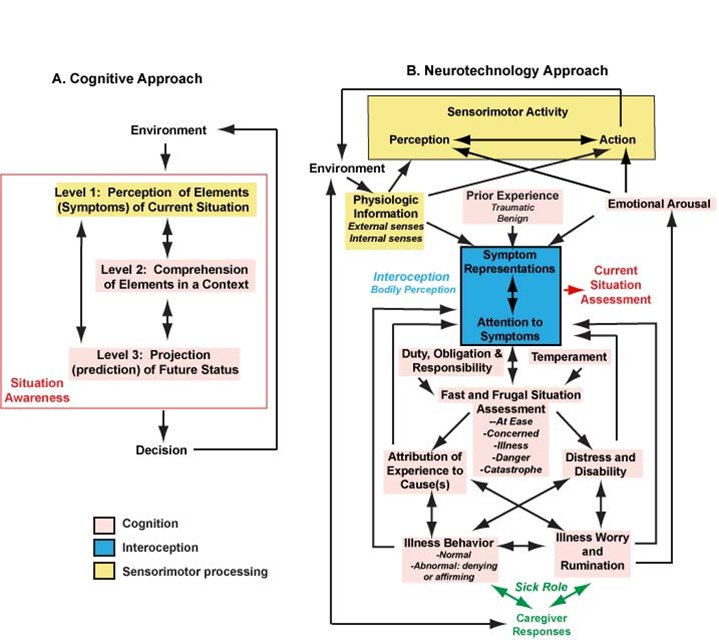

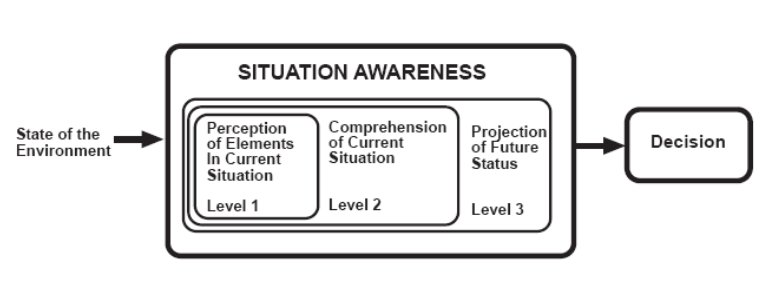

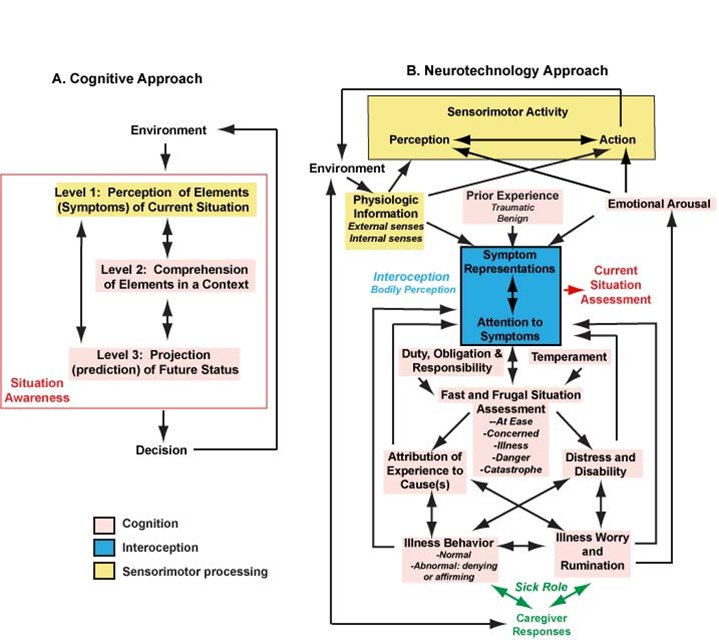

| Endsley: Nested Hierarchical SA Levels |

| |

|

- Level 1: Perception of Elements of Current Situation

- Level 2: Comprehension of Elements in a Context

- Level 3: Projection (prediction) of Future Status

|

| |

| SA Level 1: Perception of Elements in Current Situation |

| |

What’s a mountain goat doing in the clouds?

|

| |

| SA Level 2: Comprehension of Current Situation |

| |

|

| |

| SA Level 3: Projection of Future Status |

| |

I’ll tell you what it means, Norm. No size restrictions and forget about the limit…

|

| |

| Endsley: SA as Updated Situation Model |

| |

|

| |

Situation Awareness (SA) as Knowledge and Active Process

- “Operator SA comprises detecting information in the environment, processing the information with relevant knowledge to create a mental picture of the current situation and acting on this picture to make a decision or explore further.” Karen T. Garner and Thomas J. Assenmacher, Journal of Electronic Defense 19 (1996) 42-45.

- “Ability to maintain awareness of surroundings, current location, events, the environment, crew members, assessments of psychosocial conditions affecting the operation, and more.” Randy Okray, Fire Engineering 151 (1998) 12-3.

|

| |

Situation Awareness (SA)

- “…the term situation awareness should be viewed as just a label for a variety of cognitive processing activities that are critical to dynamic, event-driven, and multitask fields of practice.

- “Second, it appears to be futile to try to determine the most important contents of situation awareness, because the significance and meaning of any data are dependent on the context in which they appear.” Nadine B. Sarter and David D. Woods, Human Factors 37 (1995) 5-19.

|

| |

Properties of Situation Awareness

- Vary in spatio-temporal scope from local to global

- Regions of space

- Time windows

- Involves three realms

- Environment

- Physical features

- Actors and processes

- Perception of Elements: Model of situation within sensors and algorithms

- Comprehension and Projection: Mental model(s) of scenario(s) in mind(s) of participant(s)

|

| |

Scope of Situation Awareness

- Omniscience versus Role-specificity

- What do I need to know to do my job?

- Division of Responsibility

- First responder situation awareness – where the ‘rubber meets the road’

- Local incident command level

- State level

- Interface with Mutual Aid resources

- Issue of Trust

- Responders will try to respond based on local and personal SA

- Command trusted to provide global picture on a ‘need to know’ basis

|

| |

| Situation Awareness Evolves |

| |

|

Counterbalance responders

Reconnaissance / intelligence to improve SA

( ^ or ? ^/v )

Mitigate event (including role conflicts)

|

| |

Role Conflicts:

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

When it’s a weapon of mass destruction, hazardous material is the weapon. It’s my crime scene. I don’t want you to come and wash it away or police it up. I want you to leave it there so that I can perform my law-enforcement function—collecting and analyzing and trying to figure out who put it there.

—Law-enforcement panel member

|

| |

Endsley Model Components of Situation Awareness

-

Perception of Elements

- Comprehension of Current Situation

- Projection into Future

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

We had an incredible amount of debris inside the Pentagon from the jet fuel burning. It dropped all the ceilings and walls. They all dropped into the corridors. So we had a four-foot, five-foot-high pile of debris to crawl over to actually do any firefighting. There were a lot of hazards there.

—Firefighter-special-operations panel member

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

In a collapse like this, you have so many unusual situations. We had jet fuel, we had battery acid, asbestos, products of combustion, lead paint, silica, biological—things that are all okay individually when you run into them. When you throw them into a collapse environment where you really don’t know how much, what’s broken open, what’s not, what’s mixed, what it’s touched, what hasn’t—all those things aren’t that simple to just sort out. Some of the people wanted to come in their specialty areas and say, “Well, let me tell you about this.” [One might ask,] “Well, what does it do when it’s affected with that?” “Well, I really don’t know.” So these things aren’t quite as pigeonholed [in this situation] as they are sometimes.

—Firefighter-special-operations panel member

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

The scale of a terrorist event can have a psychological impact and erode procedures, as indicated by the following comments made by firefighters:

All we were worried about was getting our guys out. Our main concern was to get guys out. Even a paper mask didn’t matter to us.

From what I saw in New York, at least the first week there, these guys went through something that was just unimaginable, and they didn’t really care one bit about their own safety, their own health, they just didn’t care. It wasn’t part of their equation. The guys just worked and worked and worked and had no regard whatsoever for their own safety. They cared about the guy next to them. They didn’t care about themselves at all. They just didn’t care.

The World Trade Center was such an enormous event that it caused, at least in our minds, you to weigh hazards. Our first concern was having something fall on us. So you start assessing real immediate mechanical hazards: “This building could still collapse. The thing on top of [Building] Five may fall.” That overshadows concerns about carbon monoxide because it’s in the immediate.

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

I never put my bunker gear on from day one. Most I ever had was my bunker coat and my helmet, because I knew that if I walked around in that debris for one to two hours, my feet were done in bunker boots.

—Firefighter-special-operations panel member

|

| |

Properties of Situation Awareness

- Perception of Elements

- Comprehension of Current Situation

- Projection into Future

|

| |

Event Structure Perception (Zacks and Tversky, Psychol. Bull. 127 (2001) 3-21)

- We observe continuous stream of events and contexts

- We perceive temporally distinct events and contexts

- At a workstation, a person is scanning scheduled tasks or deeply engaged in a task

- In a car, driver is ‘passing’, ‘preparing to stop’, etc.

- A policeman at a traffic stop is looking for certain characteristics of a situation and actions of a suspect

- Airport security (TSA) personnel are screening for immediate threats in carry-on items with long-term goal of preventing terrorist actions

|

| |

Event Structure Perception and SA

- Element perception

- Dishes, sink, person, sponge, dishpan, drying rack

- Element comprehension (parse events in context)

- Water running, movements associated with washing dishes

- Projection of future behavior (parsed events)

- Completion of washing one dish -> repeat activity

- Turning off water -> finished washing dishes

- Pick up dish towel -> will dry dishes

|

| |

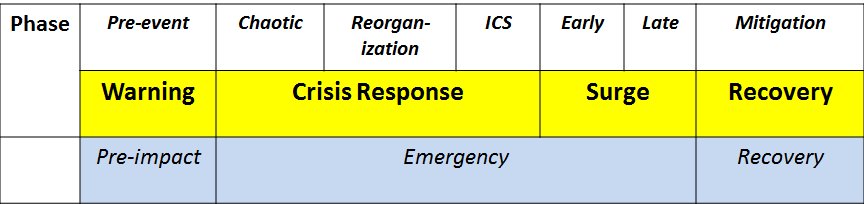

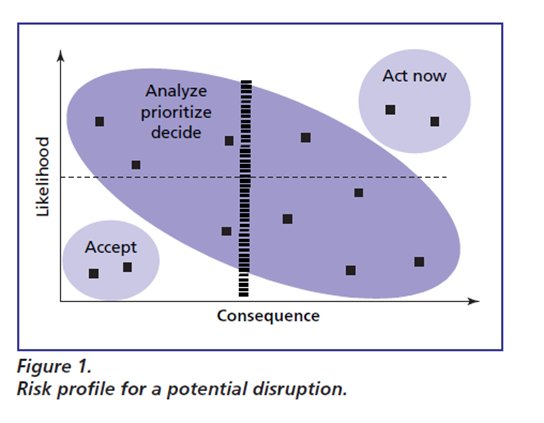

Comprehension and Projection into Future

- Instantaneous assessment of critical infrastructure and assets

- Criticality shifts with the situation

- Varies with the stage of the event

- Implicit underpinning of decision making: Necessary for understanding

- Potential consequences and outcomes

- Likelihoods of each consequence or outcome

- Relevant questions

- What are the present vulnerabilities? Are they changing?

- Which actions are required with urgency?

- What do I need to monitor carefully?

- Which aspects of the situation are benign (e.g., safe)?

|

| |

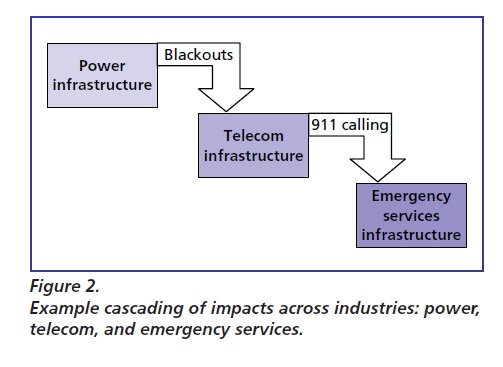

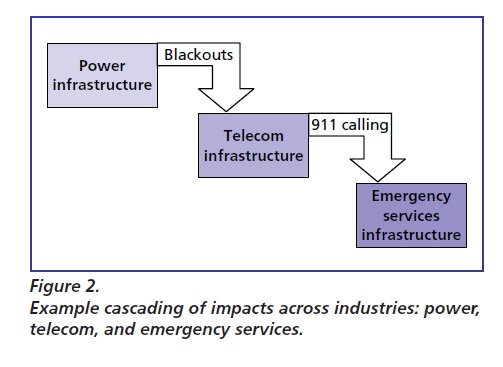

Critical Infrastructure Vulnerability (Conrad et al. Bell Labs Technical Journal, 11: 57-71, 2006)

- Telecommunications: Congestion or disruption of key communications nodes by fire, wind, water, or sabotage

- Power: Blackouts caused by insufficient generation to meet demand, transmission bottlenecks, or equipment outages

- Emergency services: Demand greater than response capacity (e.g., during high consequence event)

- Water: Contamination with toxic substances

- Agriculture and food: Contamination of food supply

|

| |

Critical Infrastructure Vulnerability (Conrad et al. Bell Labs Technical Journal, 11: 57-71, 2006)

- Chemical industry: Explosions, release of toxic gas clouds

- Nuclear facilities: Accident, release of isotopes, terrorism

- Defense industrial base: Supply line interruptions

- Banking and finance: Disruption of electronic payments systems that cause bank liquidity problems

- Public health: Pandemic, bioterrorism (e.g., anthrax), environmental pollution

- Government: Disruptions in operations

|

| |

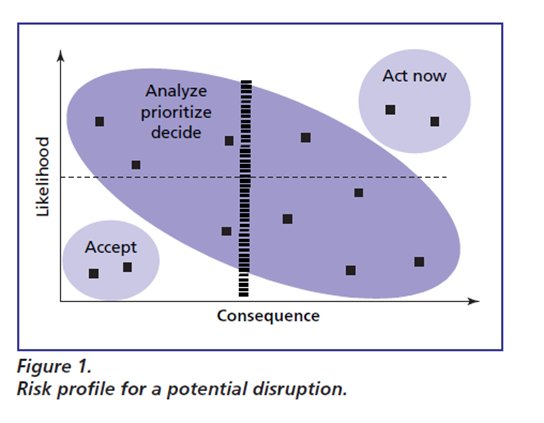

Comprehension of Consequences and Outcome Likelihood: Needed for Decision

- Conrad et al. Bell Labs Technical Journal, 11: 57-71, 2006

|

| |

|

| |

Identifying Critical Infrastructure

- Conrad et al. Bell Labs Technical Journal, 11: 57-71, 2006

|

| |

|

| |

Situational Awareness and Bounded Rationality

- Bounded rationality: “tak[es] into account the simplifications the choosing organism may deliberately introduce into its model of the situation in order to bring the model within the range of its computing capacity.”

Herbert A. Simon, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 69(1955):99-118

|

| |

Limitations of SA Implicit in Definition of Bounded Rationality

- Cognitive limitations of individual humans

- Limitations imposed by the structure of the environment

- Limitations imposed by the structure of the perceived solution space

|

| |

Limitations Implicit in Bounded Rationality

- ‘Satisficing’ (Simon, 1955) sets a solution criterion and ends the search as soon as the criterion is encountered

- Not comprehensive or exhaustive

- Not optimal: ‘just good enough’

- Limited solution space: Uses only available and ‘reliable’ information

- Experience (or training) influences process

|

| |

Bounded rationality and event management

- What critical features (re: consequences) do I need to know?

- What do I know?

- What don’t I know?

- How will I find out? Direct and indirect (proxy) information.

- What is knowable? What is unknowable?

- Which features are irrelevant?

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

One of the differences here, as we talk about terrorist events, is, this is not your average fire. There’s no [fire] getting knocked down in 15 to 20 minutes, go take rehab . . . and go home. These are long-term events, and first-alarm units, at least with us, were on the scene for hours, taking the gear off, rehabbing somewhere in the general area where they were working, finding another [air] bottle somewhere and refilling it. . . . In terrorist-type events, they’re going to be campaign, long-term incidents where people are going to be using this gear and putting it back on wet, half-used bottles—going through a lot of things that we would not consider the norm.

—Firefighter-special-operations panel member

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

We had body temperatures at night of 104, 105 degrees that were coming out of [the Pentagon]. We had people who actually succumbed to seizure-related heat exhaustion. The heat exhaustion was due to the extensive, excessive heat that was in the building, and long carries of hose and long carries of equipment with the very heavy equipment they were wearing. They were in it until their bottles would run out, and then they’d have this long retreat. In the rescue mode, they would change [air bottles], and go back in. They worked until they dropped.

—Emergency-medical-services panel member

|

| |

Examples from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

High levels of uncertainty surrounded the responses to the anthrax episodes in autumn 2001, making the appropriate personal protection strategies difficult to execute, said several members of the law-enforcement and health-and-safety panels :

—One thing my team noticed when we went to treat a postal worker was that the information kept changing daily as to what the recommendations were. And how do you treat them, how do you protect them?

—The main challenge for hazard assessment at the anthrax sites was getting accurate information on the nature of the risks. The other difference is that at the World Trade Center we could identify the source of the contamination. But with the exposure to anthrax, it was [like] looking everywhere at the same time.

—The problem is, you can’t assess the damage by just being there, like you can with something else. With the World Trade Center, you know what you have. It’s totally different [with anthrax]. You’re not even sure if you have a problem when you get a call for anthrax in the post office. . . . You can’t see the hazards you’re dealing with.

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

Firefighting equipment is designed well for firefighting operations that typically last 30 minutes, 40 minutes, or an hour. But when you have fires burning for six, eight, nine weeks, bunker gear gets to be pretty cumbersome.

—Firefighter-special-operations panel member

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

The only way you could theoretically keep anybody from getting a pulmonary exposure in these events is to keep them on an SCBA 24 hours a day for the duration of the event, which is absolutely impossible. So you’re going to get exposed, no matter what. It’s just a matter of how much of an exposure you’re going to take on.

—Firefighter-special-operations panel member

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

[The respirator] was uncomfortable. I was afraid it didn’t have a good seal, so I broke the seal. I spent about 20 hours at the scene. I wore a P-100 with those little cartridges. I still was uncomfortable, I kept going like this [gestures with back and forth motion like a trombone player], fooling around with it. I kept saying to myself, “I don’t know how those folks working in the pile, doing heavy labor, could do it with any type of mask.”

—Health-and-safety panel member

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

The problem that I saw from being there . . . was people would bring in respirators but they would only bring in half of it. They wouldn’t bring in the cartridges, or they’d bring in just what they had on scene. And these would get distributed in certain ways, but we were having a real tough time just matching everything up.

—Firefighter-special-operations panel member

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

[A respirator] has to be comfortable and noninhibitive. From a supervisor’s point of view, I have to be able to talk to my guys. If I [sound like] “blah blah blah,” then five times a day I’m pulling it off just to tell them something. Next thing you know, it comes off one time and it doesn’t go back on.

—Firefighter-special-operations panel member

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

The full-face respirator worked the best. As a hazmat team member, I have a full-face respirator. So when everybody else was looking for dust masks, the hazmat team was slapping cartridges on their full-face, and they could handle just about everything. We had voice amplifiers where we could communicate. If they had just a half-face from [retail stores], their communications went down quickly.

—Firefighter-special-operations panel member

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

With the proliferation of “white-powder” and other threats posed by terrorists, front-line emergency responders are facing a much wider range of potential hazards for which they are ill-equipped:

We had anthrax letters before this event. The special ops groups had powered air purifying respirators or respirators on their apparatus to deal with [anthrax calls], as the recommended PPE. But when you get to a large event like this, we don’t typically supply APRs or PAPRs to first-response firefighters. They did not have that.

We had [an anthrax] scare in our building. We were downstairs, so we suited up and went upstairs. When we got upstairs, PD was there, and they said, “Oh sorry, we took care of that already.” They were just in their regular uniform and we were dressed up in PPE.

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

In the first two or three days, as far as levels of asbestos, silica, lead, any of the other metals that would have gone airborne, I have no clue . . . because we were denied access to the [World Trade Center] site. We were prepared to sample, but they said, “Thanks, but no thanks.” About a week or so into the incident, when everybody started noticing that we finally had a chance to hang our sample pumps around, everybody started asking about what they were breathing the first couple of days. Couldn’t tell them.

—Federal-and-state-agency panel member

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

Hazards(1)

—There was an eight o’clock safety meeting every morning. There was a nine o’clock contractor meeting every morning. Then there was an afternoon safety meeting and an evening contractor meeting. Then there was the six o’clock meeting at Pier 92. And, on top of all of that, the Fire Department and Police Department had an operational meeting every morning at seven o’clock, at a location that was completely different than where the other two meetings were going on. So it would be hard to get any work done with all the meetings. Eventually, everybody realized what was going on and said, “Okay, we have to try to put it all together,” and they did. But it did get a little out of hand at first.

—[Information] would change day to day. We ended up hiring a temp . . . to do nothing but monitor all the different sites from DoD to IAFF to IAFC, CDC, NIOSH. I gave them a list of web sites and I said, “You just [put] these in a circular and you keep giving them to me so I can try and keep up with what the hell everybody’s saying.”

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

Hazards (2)

—You had a lot of entities that had their own specific mission, whether it was the EPA or the military, the FBI, the USAR teams. They all had their own unique perspective of what constituted a hazard, and what was a significant concern to them may not be a concern to another group. They all had good intentions of putting forth their information, but at times it became unnecessarily complicated. We would have crews that would go in at a certain level of protection, working right next to crews that were in an entirely different level of protection. There were questions about which one was right.

—The thing that drives me crazy, and I hate to say it, but all the experts have got to come up with a common theme. I can’t have [one federal agency] telling me, “You need Level A protection for this,” and [another agency] telling me that a half-faced respirator and latex gloves are sufficient.

|

| |

Example from Protecting Emergency Responders: Lesson Learned, RAND Sci Tech Policy Institute, 2002

Safety briefing for SA

I guess it was about day three or four that [a person at the Pentagon response] actually but together a safety team briefing, because everybody had their own safety officer, if you will. USAR had theirs, we had ours, FBI had theirs, Army had theirs. So we finally put together a unified command of safety officers who met once every 12-hour block to bring back all the information and decide what was going to be appropriate safety precautions, gear, etc. . . . If you were operating here, it was going to be this. We came up with what the appropriate [PPE] level was, what filter would we wear in our filter masks. Not just the first one that you come across, but which level of filtration will be correct.

—Firefighter-special-operations panel member

|

| |

|

| |

|

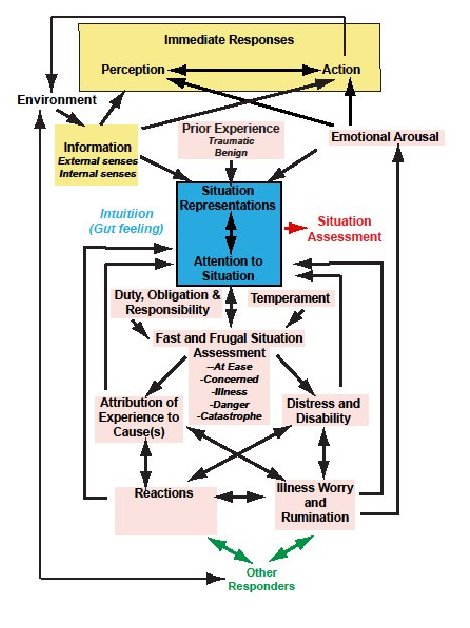

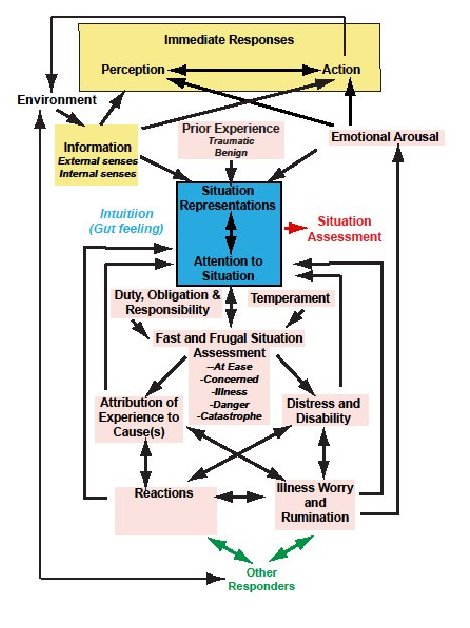

In cognitive terms, initial intuition and updates are based upon a fast and frugal heuristic (Gigerenzer and Todd, 1999; Goldstein and Gigerenzer, 1999) or ‘rule of thumb’ (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979) assessment

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47:263-291

Gigerenzer G, Todd PM (1999) Fast and frugal heuristics: the adaptive toolbox.

Goldstein DG, Gigerenzer G (1999) The recognition heuristic:how ignorance makes us smart. In: Simple Heuristics that make us Smart (Gigerenzer G, Todd PM, The ABC Research Group, eds), pp 3-34. New York: Oxford University Press.

|

|

| |

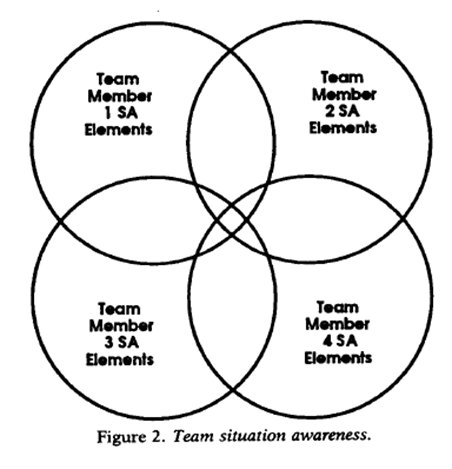

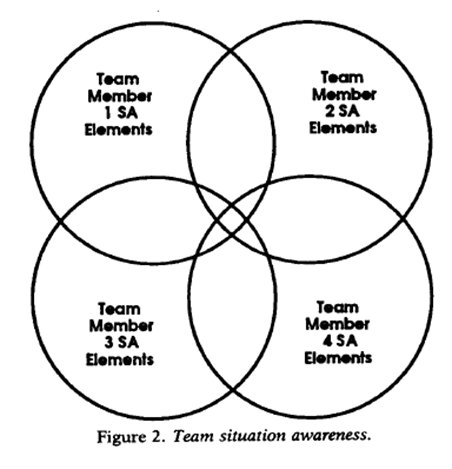

| Team SA |

| |

| Endsley (1995)

- Team SA: degree to which every team member possesses SA required for responsibilities

- Quality of team members’ SA of shared elements as index of team coordination

- Weak link: Team member lacking SA for one element of responsibility area

|

|

| |

| Support Decisions During Low SA |

| |

|

| |

| Avoid Errors Due to Low SA |

| |

Next time check my pulse—I was only hibernating!

|

| |

| Enhance SA when Necessary |

| |

|

| |

Enhancing Situation Awareness During Crises

- Decisions / responses depend upon SA

- Requires recognition of properties of decision making

- Requires recognition of limitations of available information (particularly during a crisis)

- Requires consideration of robustness and resilience of available resources in plausible scenarios

|

| |

|

| Copyright © 2011 - 2016 Carey Balaban |